In The Den with Mama Dragons

You're navigating parenting an LGBTQ+ child without a manual and knowing what to do and what to say isn't always easy. Each week we’ll visit with other parents of queer kids, talk with members of the LGBTQ+ community, learn from experts, and together explore ways to better parent our LGBTQ+ children. Join with us as we walk and talk with you through this journey of raising healthy, happy, and productive LGBTQ+ humans.

In The Den with Mama Dragons

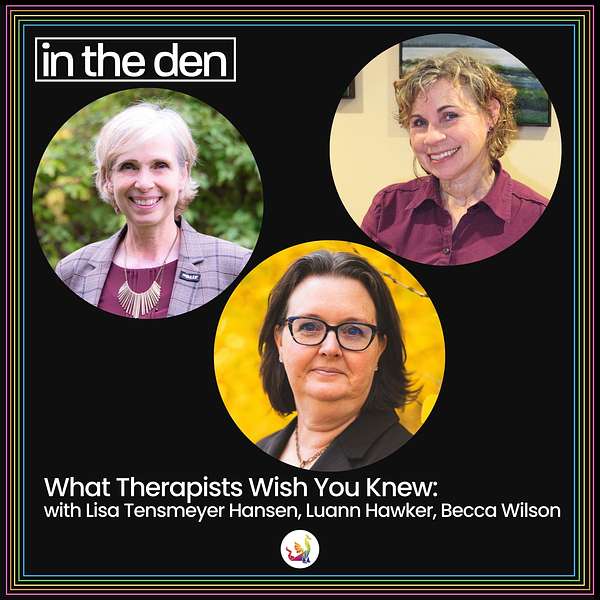

What Therapists Wish You Knew

Therapy is such a wonderful gift for so many of us that need support. This week In the Den, Jen joins three therapists from Flourish Counseling to talk about the things that mental health providers wish parents of LGBTQ kids understood.

Special Guest: Lisa Hansen

Lisa Tensmeyer Hansen (PhD, LMFT, Clinical Director) is the clinical director and founder of Flourish Therapy, Inc., (Flourish), a behavioral health clinic located in Provo, Utah, which she founded in February 2017 to meet the needs of LGBTQ+ and SSA individuals and their families. Lisa received a B.S. from Brigham Young University in 1990 as university valedictorian (Summa Cum Laude with Honors thesis), an M.S. in 2012 and Ph.D. in 2017, both at BYU, focusing on improving the mental health of LGBTQ+ people in conservative families and communities. She lives with her husband in Payson, Utah, where together they made a home for 7 children (and a few extras) and now have 18 grandchildren.

Special Guest: Luann Hawker

Luann (she/her) is a licensed clinical social worker. She has worked as a therapist since 2019 and joined the Flourish Therapy, Inc. team in August 2020. She has over 25 years of volunteer experience with children, adolescents, and LGBTQ+ advocacy work. She currently serves on the board of directors for Genderbands, an international non-profit organization that serves the transgender and non-binary community. She has clinical experience counseling individuals, groups, families, and couples. She completed a Bachelor of Science in Psychology in 1995 and a Master of Social Work in 2021. She has been with her spouse for 30 years and is the mother of four adult children.

Special Guest: Becca Wilson

Becca Wilson, AMFT, graduated from UC Berkeley in 1989 with a bachelor’s degree in Applied Mathematics and from Utah Valley University in 2023 with a masters in Marriage and Family Therapy. She started her work in mental health as a volunteer as a text line counselor with the crisis text line, which prompted her to return to school and establish a second career in mental health. She has six children, most of whom are in the LGBTQ population. Becca loves hiking, puzzles, movies, nature, animals, and people. She enjoys playing final fantasy weekly and watching anime with her kids.

Links from the Show:

- Flourish’s website: https://www.flourishtherapy.org/

- Join Mama Dragons today: www.mamadragons.org

In the Den is made possible by generous donors like you. Help us continue to deliver quality content by becoming a donor today at mamadragons.org.

Connect with Mama Dragons:

Website

Instagram

Facebook

Donate to this podcast

JEN: Hello and welcome to In The Den with Mama Dragons. I’m your host, Jen. This podcast was created to walk and talk with you through the journey of raising happy, healthy, and productive humans. Thanks for listening. We’re glad you’re here.

Therapy is such a wonderful gift for so many of us who need support. I’m a huge fan. Honestly, I think everybody who can go should try therapy if they get the chance. But many of us take our LGBTQ+ children to therapy for a multitude of different reasons. And while we’re entering this world and navigating it with our children, we sort of think it would be amazing to learn from the people who are treating this wide and diverse population of queer people? Wouldn’t it be wonderful to get some short-cut tips? Well, today, we’ve got you covered, In the Den.

We asked the therapists from Flourish Counseling what they wish the parents of their queer clients understood. And they delivered some genius wisdom. Today, we brought three of their therapists here to expand and help us LEARN what our kids need us to learn! So, welcome In the Den to Luann Hawker, Becca Wilson, and Lisa Tensmeyer Hanson.

Luann Hawker LCSW has over two decades of volunteer experience with children, adolescents, and LGBTQ+ advocacy work. She has completed her Bachelor of Science in psychology in 1995 and her Master of Social Work in 2021 with additional coursework in gender studies. She has clinical experience in individual and group counseling for anger management, domestic violence, substance use disorder, DBT, and trauma-informed therapy.

LUANN: Thank you.

Becca Wilson, AMFT, started her mental health work as a volunteer with the crisis text line. This led her back to school to work professionally in mental health. She has experience in counseling individuals, families, and couples. She is trained in brain spotting and internal family systems. She graduated with her masters degree in marriage and family therapy.

LISA: Perfect. And what you should know about both Luann and Becca is they each have a variety of queer children.

JEN: Okay. That’s going to be helpful because we’re talking to the parents. Our third panelist for today is Dr. Lisa Tensmeyer Hansen who is the clinical director and founder of Flourish Therapy, Lisa received a B.S. from Brigham Young University in 1990 as university valedictorian (Summa Cum Laude with an Honors thesis), an M.S. in 2012 and Ph.D. in 2017, both at BYU, focusing on improving the mental health of LGBTQ+ people in conservative family and community.

I encourage all of our listeners to go and read their longer bios in our show notes. These are some seriously impressive women and we can have all confidence with the ideas that they share with us today! So, welcome ladies. Thanks for joining us!

LUANN: Thank you.

BECCA: Thank you.

LISA: Thanks for having us.

JEN: All right. So here’s what we’re going to do. I am going to read these wishes that the therapists submitted and I’m hoping you guys will just kind of elaborate, expand. Honestly, they were so articulate in the responses. That I’m hoping we have a chance to go deep because I think our parents, I genuinely believe our listeners really, really, really want to understand and do the best they can for our kids. And this is a chance to get some free therapy and some insight, some short-cuts into parenting. So I’m just going to read, like direct quotes and then you guys can pitch in. Does that make sense?

LUANN: Yes, it does.

JEN: Like a fun game. OK. Here’s our first one. “I wish parents understood that all too often their queer children are forced to adapt to spaces and situations that are not accepting of who they are at the core. The burden then lies on the child to tolerate feeling unaccepted -- and this is too great a burden. Parents may think they are asking for a small accommodation, but it always comes on top of the great burden that their child is already carrying alone. Parents who create an expansively supporting environment reduce the burden the child is already carrying.”

LUANN: Yes to all of that. I absolutely share that wish. As parents, we need time sometimes to adjust and understand and learn what our queer kids need. But that is on us, not on them. And so if we’re going through that journey trying to educate ourselves, trying to understand things, it’s best to listen to our kids and what they need and roll with it even if we don’t understand it yet. I might not understand why my child wants those pronouns or this name or different clothing or whatever it is. But it’s important to listen to them.

LISA: One of the ways I think this manifests, is that the child actually, is starting to recognize they have a different culture than the family does. And they recognize the difference between their personal culture that’s developing maybe internally and what the family is. And so they already feel that burden of that separation. So when parents are asking them to come closer to the family culture, a child can feel invalidated because they haven’t even been able to share or have their own developing culture separated. And Luann’s given us some good ideas about how children usually start to say, “I feel a little bit different.” And as soon as a child asks for something like that, you can anticipate that behind it is a huge pile of “My culture is different and changing and I am worried about this difference.” And that’s the burden that that wish describes that the child is already feeling. Parents sometimes are like, “This is a whim. This is a nothing.” No. There’s something behind this that’s bigger than a parent is likely to see.

JEN: I think about how easy this is for parents because if there’s a contentious or a stressful situation we’re going into, maybe a social gathering in the community or maybe an event in our church community, we can’t really change everything. So it’s a little bit easier to ask the kid, like, “If you could just please wear pants, that would make it so much easier for all of us.” Right. But this therapist so beautifully articulated that you’re putting this huge burden on a child. And it’s just so easy for me to see the parent’s side of, “Oh, yeah. We do sometimes try to control our kids because that seems so much easier than facing that relentless pressure.”

BECCA: I think, when I heard that wish, what came to my mind about burden, is the burden that kids face in school being LGBTQ. And when you look at those statistics of the difference in the experience that LGBTQ kids have in public – or any schools really – versus cis/straight kids. It’s huge, and it’s scary, and it’s disheartening. And I think it’s important, like we want to be optimistic and we want to think that everything’s okay with our kids. And I think so much so that it’s almost at the expense of our kids feeling like that the parents can’t handle what burdens they’re carrying or what difficulties that they’re experiencing. And so parents being able to keep their communication lines open with their kids and creating the space where kids feel like they can come to them with anything is really important because that burdening feeling is one of the things that is most often present among kids that are suicidal. And we know that suicidality is much higher among LGBTQ kids.

LUANN: I had another thought as well. It’s developmentally appropriate – not just for queer kids, but for any kids – to start differentiating themselves from their parents. And that can happen maybe in different ways for queer kids or maybe not different, maybe it’s very similar. It can be a differentiation from those cultures that Lisa was talking about. But we have an opportunity as parents to celebrate when our kid reaches that stage where they're kind of looking at stuff and trying to figure out if it’s a good fit for them and evaluating that. And it might be a little bit painful as parents if they choose something different. But I still think we can celebrate that independence and that empowerment that our kids have in small steps along the way because that is going to help them on their road to adulthood and set them up for success to be able to make some of those decisions and express some of those things that they’re noticing about themselves to their parents and their families, and their community and all of those things. So I think it’s helpful to remember that this is a healthy thing for kids to do to be able to say, “I need this space to be different.”

LISA: And that sometimes comes into conflict, like Jen pointed out, with church things. Like, if you could just adjust this, we’ll all feel a little bit more comfortable in our ward community. Or, “If when we go Grandma’s, if you could wear your hair like a girl instead” That kind of thing that it feels like we’re just asking a child to make adjustments, isn’t that easier than asking Grandma to make adjustments. But what actually happens, then, is that the child takes on the entire burden. And they recognize that mom and dad, or whoever is asking this, is not having their back. And that makes a difference in their relationship. It changes things.

JEN: Here’s our next quote: “I wish parents understood that it is always the right choice to choose compassion over orthodoxy.”

BECCA: It’s sad that that has to be a wish. It’s sad that that’s not a no-brainer. But it’s absolutely true that rules and checklists really don’t serve our kids well, our families well. They don’t serve us well.

JEN: Can you break it down for us? Like, what does it mean, like, I’m the mom and I’m asking you what does it mean if I’m choosing orthodoxy? What does it mean if I’m choosing compassion? You’re telling me one is better. I don’t even know what they mean.

BECCA: So, orthodoxy to me means conforming with social norms to choose rules that serve check lists or thinking there’s a right way to do things. Versus compassion is looking at the situation, at the individuals involved, and looking for where compassion is needed, looking for which individuals are hurting, which individuals have less power in the situation. And showing compassion would be giving more power to those individuals. It would be favoring and listening to them, giving them space to be seen and heard. And if that means not following the rules, or checklists, or social norms, then you choose compassion over that.

JEN: It kind of makes me think – this is biblical so nobody be offended that I’m talking about the bible – but it kind of makes me think of that good Samaritan story where they had rules about who could be touched and who couldn’t, or the ox in the mire, or all of those examples in the scriptures where we knew the rule and the rule was pretty strict. But in the scriptures, the good guy – Usually Jesus but sometimes someone else, right – is choosing the compassionate, empathetic direction instead of what the orthodox rules might say.

LUANN: I like that you used the word empathy because that’s the word that comes to my mind most on this wish as well. Orthodoxy doesn’t always, but for me often implies some sort of religious context. And more than once within religious contexts, I’ve heard sort of a caution against too much empathy which always has struck me as really interesting. And not the place that I personally want to be and not where I would encourage parents who are trying to understand their children to be. We need that empathy. We need to prioritize that if we are prioritizing the loving of our children.

LISA: The quality of healthy relationships is generally, not in how well things are going, but in what happens when expectations are not met. And what we’re talking about here often is parents recognizing that their children are not meeting some expectation of what a parent said is going to be your best life. There’s something that’s happening that the parents are trying to figure out how to guide a child into the best life. And, if what they choose to do is emphasize behavior and rules and social norms, they will have less of a relationship there than if they emphasize compassion and listening and how is what is happening in your life different from the expectations I have and I want to learn from you. And then I’ll offer some guidance and hopefully we can find a place that comes together. Rather than, if you don’t do it my way, you’re going to have a poor life.

BECCA: Well said. I love that.

LUANN: Yeah.

JEN: Awesome. Anything to add before we move on to the next quote? No. This one’s kind of long. “I think so many parents have anxiety around discrimination that their children might face if they are sex or gender minorities and so discourage the kids from living authentically in a misguided attempt to protect them. They become the actual ones who make their child feel like they have to put on a mask in order to enter the world, which makes the child feel like the world is more important – or the judgment of the world, I guess – is more important than what is really inside them.”

LISA: What we want in the long run are children who are trusting themselves, not children who are always looking outside of themselves to see who they should be and how they should be. When they really start to trust themselves, then they get in touch with the deepest values within themselves. And they are less emotionally reactive. They have a better sense of future. They’re less suicidal. And so, as a parent tries to help a child trust themselves and identify their emotions and their feelings, identify their hopes for the future, that they can actually support that in ways that help alleviate what you just told us about.

BECCA: I think, also, that in general, this is probably good advice for any parent, but even more so for parents of LGBTQ children is that, to check the parent’s emotions and make sure that they are handling their own emotions and not imposing them on the kids. So, if they have anxiety about discrimination, which is totally valid and needs to be expressed and needs to be thought through, processed. That needs to happen with some safe place for them, but not with their kids.

LISA: So true.

BECCA: That’s one huge way that they can protect their kids. And that actually applies to not just anxiety of discrimination but a whole host of other things. Now, that’s not to say that, if your kids come to you with anxiety of discrimination that you’re supposed to gloss over it and whatever. But to let that experience be about the kid’s emotions and supporting them by listening and hearing and seeing them. And, like Lisa said, helping to allow them to trust their own judgment.

LUANN: I think this question links pretty closely with the first question we discussed on placing that burden of a space that feels better. But I really like what Becca was saying about encouraging parents to regulate their emotions before they approach their kids on this. I try to make sure I’m in a place where I am not putting my anxiety on my children. If they are excited, enthusiastic about the way they’re presenting themselves and the way they are moving around through the world and interacting with people, I want to encourage that confidence. And if I come in and say, “Well, you might get some side comments or people might not react well to that.” That can be so deflating and discouraging and harmful. And there’s the possibility that the next time, they won’t be as ready to – I don’t want this to be a fear-based kind of thing – but the possibility is it can damage my connection with them. And they are less likely to come to me for input or support or to celebrate with them and to feel validated and loved. All of that is at risk if I let my anxiety shape their interaction with the world and their community.

JEN: It’s interesting that you say that, because I can think of a few specific times in my own childhood where I was feeling like I nailed it, like I was lookin’ good. And then it only takes really one comment for you to second guess yourself the entire day and make huge efforts to fit yourself back into a box that’s very uncomfortable so that you don’t experience that again. And if they were that profound that I can remember when I’m old, I can’t imagine how intense that would be for kids who are just experimenting and branching out, especially in ways that are counter-culture to the family. Because in my case, it wasn’t even like big stuff. It was like a new experimental hairstyle or whatever that wasn’t so much about personal identity. But like what you said, Luann really rings home to me, the idea of sending our kids out into the world with all the confidence that they can muster because the world isn’t always kind. You want them to have that from home. All right. Are you guys ready?

LISA: I just want to say one other thing to underscore what Becca said, too. Because I want to validate that parents do have fears and concerns. They want their children to be safe. They want their children to experience connection with other peers. They want their children to feel accepted and have a chance to contribute. So it’s normal for parents to have these fears. But, like Becca said, those fears, you share with other parents, not with your children.

BECCA: There’s one more thing I wanted to add too which is that this is addressing the anxiety of discrimination but there’s a whole lot of other emotions. Even sometimes us as parents when we read an article or find out some news that’s really distressing and in particular abaout the LGBTQ. Sometimes parents, well-meaning thinking they’re being allies, get very upset over the news. And might even talk to their kids about it. “Oh. Isn’t this horrible.” But, depending on the kid – and this is why I guess it’s important to be in tune with our kid and have those open lines of communications – but some kids would be like, “That just makes things worse for me to hear about other horrible things happening in the world, particularly around the LGBTQ and also to see that my parent is so upset that they can barely handle it.” And I think that, in and of itself, can be discouraging to the kid for a lot of different reasons.

JEN: Yeah. We saw a lot about that with the recent passing of Nex Benedict, we heard back from a lot of parents whose kids kept asking them to please quit talking about it, or my kids don’t want to talk about it. And there’s only so much bad news you can carry at any given time, right? Alright.

“Your kids only learn to hide who they are, even from themselves, when they aren't given the space to be who they actually are.” Is this true, if I lived on a deserted island, would’ve I been 100% myself because I had space?

LUANN: My first thought is, at what point did you land on that island? How much influence and socialization did you experience before you were alone on that island? And how much of that are you carrying with you? That’s a really tricky question. Even those that work very, very hard to make sure their kids have that expansive space to express who they are, we’re not on an island. They’re interacting in other spaces that have other expectations and responses and different socializing experiences. So hopefully home can be a haven where they can relax and be themselves. But they’re going to carry stuff home too, even when we’re doing the best we possibly can do – which is never going to be perfect, by the way. We’re all going to mess it up to some degree. That’s just something as parents that we have to accept and try and learn and do the best we can to create that space and listen to our kids when they say, “Hey, I need something different.” But even in the best of circumstances, there’s going to be stuff that they encounter and bring home with them that has an impact on how they feel, whether they feel safe or less safe expressing who they are.

BECCA: So, what comes up for me when I heard that statement is that, how does that happen? I think about how does that happen when they aren’t given the space to be who they are. And I think about situations where they’re having difficult emotions or they’re in distress of some sort. And it’s hard for parents sometimes at those points to just be able to stay close by and have sympathy when they’re really upset. And then wait for the cooling down. And then, when they’re cooled down, help them label their emotions and kind of make sense of their experience and process. Parents, because we’re well-meaning and because our kids were born where we had to make sure they were being taken care of – all their needs – they had to be fed. They had to change their diapers. And all of these things, we think we always have to be fixing the problem. And so sometimes our kids come to us with whatever and we’re trying to cheer them up and we’re trying to give them advice. And all of those well-meaning things don’t leave space for the kids to just be themselves. And so sometimes I think that’s how those spaces start to close. But, along those lines, here’s my little bit of hope about that. John Gottman who’s a doctor researching relationships says that parents really only have to get it right about 30% of the time to be successful.

LISA: That’s good news.

JEN: Those are numbers I can even do. That does feel hopeful. I’m telling my kids that. “By the way”

BECCA: Yeah. It’s hard not to want to use that as a scapegoat, right?

JEN: I only need to get 35% of this.

LISA: It’s important to remember, too, that part of this comes from the truth that almost everyone, given a chance, will try to pass as straight or cisgender. That is they can tell society is asking that from them, that their parents are asking that from them, their teachers. So many parts of society are making those assumptions. It’s just easier to pass if they can in some way, rather than even start to explore. So we see kids even resisting when someone calls them a name that suggests that they’re anything but cisgender or that they’re anything but fully this or that in some passing way. They will resist because it’s kind of like something to be afraid of until they have, perhaps, more experience or more understanding of themselves. And so, because of this pressure to pass, so many of our children actually do start to put on a straight or cisgender mask as they start to explore something else. And what this often ends up in is a comfort the child has to start making the mask I wear here and the one I wear here and this authentic space that may occupy some place in the middle. You see this show up as parents say, “My child is so dishonest. I’m seeing that my child is not able to be honest.” And I will try to help them understand, your child may feel like society does not want them to be honest, that society actually doesn’t want them to tell the truth about their experiences or their emotions or their feelings. And so at home, you have to do this even more fantastic job that Becca’s just described about making sure that your child knows that at home, they don’t have to wear a mask. At home, they don’t have to pretend to be one thing in order to pass or make you happy, that you really want their authentic self. And that will help them integrate these parts that may come across to you, dear parent, as deceptive.

JEN: I think that over the last couple of years, I’ve been able to absorb this concept that the society part is so influential because, as I talk to more and more people who grew up with queer parents, who still tried to be straight, who tried so hard to be in the closet to themselves and others. I’m like, “You had two dads. You were going to Pride as an infant. How can you get more supported than that?” And consistently, the world is not there yet, even if your house is. So we have to make our houses that safe because the world isn’t always.

LUANN: And I think that kind of goes into why we try to create a space where they can take off the mask and be their authentic self. But it’s not helpful to demand that. Everybody gets to decide their level of outness, what circles they’re out to, the pace of that. That is a very individual choice and that includes to parents, to peers, to every level of those possibilities. They get to decide that. Not us. Never, never us as parents.

LISA: So true.

JEN: “When you have a choice between fixing behavior or healing the relationship, always choose healing the relationship. A good relationship impacts behavior more than fixing behavior impacts behavior in the long run.”

LISA: I’m just going to say that behavior is almost always a factor of the relationship. Children tend to emulate their parent’s values and behaviors when their relationship is really strong. So, I always encourage parents to look at the aspect of what’s working in a relationship before trying to fix behavior.

JEN: The way this is worded almost makes me think of maybe your child’s doing poorly in school or maybe your child is participating in some dangerous sexual, risky behaviors or using substances. And this therapist is maybe encouraging therapist – you guys have to tell me if I’m reading it wrong – but instead of worrying about the drugs, instead of worrying about the F’s, start first back at the relationship.

LISA: Correct.

JEN: Is that what you guys mean?

LISA: And what we usually get the complaints are, “My child spends all of their time in their room. My child is not participating with family. We want to go some place and they are not going. So we’re starting to insist that they go with us to church and insist that they go with us here. We’re starting to insist on these behaviors because it’s impacting their brothers and sisters.” That’s really typical. And so, starting with what’s happening in your relationship with this child, Luann said, too, we’re not really in charge of how that happens. But we will get children’s emotions at some time. We will. And their emotions are always a bridge. They seem like barriers because they seem to come with accusations or with rejections. But our children’s emotions are always a bridge. If we can find a way to do as you heard described today. Let them deescalate in a way that they can feel our compassion and then help them identify the feelings that they have, that addresses all of these things. That creates relationship. That makes it more likely that our children will want to do what we’re doing or at least talk to us about what aspects of it they can stand and we have a better chance of connecting.

BECCA: That statement brings up for me is that there’s always a reason for behavior, whatever it is, good or bad. And I shouldn’t say good or bad. I don’t like that categorizing. But behavior that’s perceived by parents as difficult or unhelpful versus behavior that they perceive as being cooperative and desirable. But there’s always a reason. And so often the reason is maybe some emotion or something that the child is going through that they don’t feel like that they can resolve or process or even talk to about with their parents. And that’s often because the relationship isn’t there. And then what research has shown, is that the number one way that deep bonds are created is through that process of when they are in a distressing or difficult emotion to be able to be there and be patient. And then, when they’re calmed down, to help label their emotions and process what’s going on.

JEN: “It would be nice if parents understood that we are not to mold our children into any particular or specific thing. Our job is to guide them to becoming the best version of themselves as they are born to be, not as we want them to be. They don't need to be fixed and we are here to help them find the tools that work for them in their struggles.” I told you guys these were good.

LISA: As we look at literature throughout the centuries of time as people talk about their experiences with their growing up and parenthood. This is the universal question, is “What am I bringing here? And it’s different than what my parents wanted me to be.” That seems to be as some sort of overall design that children are sparks of their parents in some way are designed to actually be different in a way that expands the whole system. And yet, parents – it seems, universally, over time – have a natural resistance to that because we like these sparks of ourselves actually to reflect the things we like best about ourselves and about our children. And when you add religious ideas into the mix, if there are some, that can become even more meaningful to parents. And so, backing up and saying, “Huh, how can I not be what my children write about as their resistance factor to who they’d eventually like themselves to be.” I don’t want to be the obstacle to what my child really, really wanted in life. That can help us guide.

JEN: When you say it like that, it makes me think of every story and movie where the family expects the child to become a doctor or take over the family business. This is a narrative that is the major conflict in a lot of literature and media.

LISA: Yep. For good reason. It’s not just parents of LGBTQ kids. It’s parents of just about everybody.

LUANN: So it’s interesting. This is kind of a similar phenomenon, I think. But when your kids don’t agree with you on political views or religious views or lifestyle – and I mean like what you consider dangerous behaviors versus what they consider the level of risk that they’re taking. When there’s a disagreement between kids and parents about that, when parents are accepting of those differences and are able to show, I guess, an unconditional love and that the relationship is not conditional on those types of differences, we’re seeing this there’s actually a greater – the relationship improves. And a lot of times, when the relationship improves, there’s actually a greater chance of parents and kids coming to a meeting of the minds. And so it’s kind of ironic. But it’s accepting and embracing the difference, actually is the most likely way that you become closer.

LISA: That’s a beautiful irony, isn’t it.

LUANN: Mm-hmm.

JEN: It goes with every story. As soon as mom and dad let them choose their own career, they can be friends again. It’s the theme of all the movies, right? But, to be real, letting your kid make all their own choices and have their own life is hard because when you’re the parent, sometimes you’re pretty darn convinced you know the real secret to happiness.

LISA: Well, parents do. Universally, we all do.

JEN: You did it so you figured it out and now you’re just going to bequeath that to your child.

BECCA: I think a lot of parents want to do that because they want to save their kids the heartache that they experienced, whatever it was.

JEN: Right.

BECCA: And the weird thing about life is it doesn’t work that way. Sometimes we just have to watch our kids make choices that we know might not end up in a happy ending for them. And then we just need to be there when they need comfort or whatever it is. But that’s how people learn. That’s how they grow, is by experiencing and following their own choices.

LUANN: I had a similar thought: a quote from Yoda is running through my brain. Failure is a great teacher. I don’t remember the exact quote, but I remember it from one of the movies. Failure is a great teacher. And so I think Becca’s right. Sometimes we try and protect our kids from failure, but that takes something away from them. That experience to be able to make that choice for themselves, succeed or it doesn’t go the way they planned and something doesn’t land the way they hoped, that’s how we evolve and grow and learn and discover our identity even.

JEN: I’ll admit right here that a mantra that has been in my head for about twelve years now as my kids have entered their teens and into adulthood. I just say it to myself. I don’t know if they know. They don’t listen to this, so this isn’t going to teach them. But all the time, in my head, “This is not my life. This is not my life.” Whether we’re doing a college tour or they start dating someone. “This is not my life. This is not my life.” I say it a lot. “This is not my life.” Letting them have their own life is hard.

LUANN: Yeah. It is hard to watch them doing things that scare you.

LISA: Yes.

JEN: When I played Barbies, the Barbies all did exactly what I wanted them to do. If I had a baby, all this parenting practicing is kind of a lie.

LISA: I wanted to say too, that when our children are embarking on something that we have doubts about, if they have difficulties, they will probably only come talk to us about them and get our input and advise if they’re not afraid that we are going to tell them “I told you so” or “This is too hard.” Or give some skeptical opinion. So the secret is, as a parent when you’re in this position and you say, “What do I do? What do I do?” I invite parents to say, find and focus on what it is you really enjoy about your child so that you’re not finding and focusing on just the worst-case scenarios or the ways things are going to go wrong. If you can focus on what you enjoy, then when you’re with your child, you can look for that. You can talk about that. You can express that. It’ll make all the difference in your relationship with your child.

JEN: I love that. We could pretty much just keep going on this topic. But I’m going to throw in this therapist's wish because I think it goes along with how this part has evolved. This therapist says, “I wish that parents understood that it is okay to make mistakes. The real power of relationship healing is not in not making mistakes, but in owning mistakes without justifying them and modeling healthy accountability and apology behaviors.”

LISA: More important to repair than it is to do it right in the first place. Parents who never make mistakes can’t teach that to their children.

JEN: Also, those parents don’t exist.

LISA: Nope. But we certainly have experienced – all of us as parents – moments when we want to convey to our children that it really wasn’t a mistake because that’s not helpful. It’s way more helpful to acknowledge the ways in which our message didn’t come across well and to own that, even if we meant well. That repair makes all the difference. Even if we don’t feel like we were in the wrong, really helpful just to say, “I can see that message came across really badly. I regret that.” That’s huge.

LUANN: It’s also an opportunity to model that behavior that our children can learn from us when they make a mistake in any part of their lives, in their relationship with us or with other people. If that has been demonstrated by parents, it’s much more likely that children will develop that language and that ability to own their mistakes.

LISA: 100%

JEN: What happens if they don’t. Like, what happens to people who never learn to admit that they’re wrong? Do they just drive forward knowing that it’s wrong or statistically do they just change direction and just pretend like they were wrong all along. What happens if you don’t learn this skill?

LISA: You lose relationships much faster. People don’t feel as safe with you. You don’t feel as safe with other people. Some families have a taboo about talking about anything that’s difficult. And so family members don’t really know where they stand with one another either. They don’t feel as close.

LUANN: It’s hard sometimes too because I’ve had conversations with my kids where they’ll point out, “Hey mom, when I brought this subject up and you said X, Y and Z, I felt this and that.” And in wanting to admit that I was wrong, I might put it out there in a way like, “That’s not the impact I wanted you to have. I was just saying that because of X, Y and Z.” And I love this teaching moment that my child provided for me when she said, “Mom, can you just acknowledge how I’m feeling right now about this.” and I realized, “Oh, my goodness, I’m just making the same mistake that I did in the original conversation because I was wanting them to know that this is coming from a place of love. Of course I love you. But it just comes across as a justification, you know. And so being able to just say I’m sorry it had that impact, that must’ve been really hard for you.

LISA: Explanations rarely convey what your feeling matters to me.

LUANN: Yeah.

JEN: Have you guys considered talking to some of my family members?

BECCA: Here’s the problem with therapy, you can hear all of these things in the therapy room and they maybe make sense for a moment or two. But so many people it goes right out of their head as soon as they leave the room because they’re dealing with all their own stuff and they have reasons for doing what they’re doing.

LISA: You have to practice it before the trauma response or the escalated response or the reactive response that we all have. I will actually practice, sometimes even in front of the mirror so I know I’m seriously focused on it, things that I want to remember to say that I know in the moment, I will not even remember I wanted to say something. Creating those neural pathways by practicing, just like practicing this one statement of, “Wow. I can see that my message came across so different. I really regret it because it matters to me what you’re feeling right now.” Practice saying that over and over and over so that you can come back to it. “Okay, there was something about mattering. There’s something about regret. There was something . . .” This is how our brains work. It’s Okay.

BECCA: Sometimes I do prep my clients for failure by saying, we’ve talked about this. Now, when the situation comes up and you don’t remember it until maybe a day later, after the situation has happened. Don’t beat yourself up for that. Just process how you could’ve done it differently.

JEN: We all do that, right?

BECCA: Yes.

JEN: I wish I would’ve said.

LISA: Yep.

JEN: If only I had said . . .

LISA: Cute Becca.

JEN: All right. I think we have time for one more. Are you ready? And I feel like this comes up all the time. I can just picture the parents that these therapists are talking to. “I wish parents understood that kids are going to work through their own struggles at their own pace, in their own time. We can never dictate, change, or hasten the process. And all kids can find their way through hard things with time, tools, and the space to do so.”

LISA: That illustrates the beautiful principle of believing in your child. And children have the sixth sense of whether a parent believes in them. When a parent starts from a place of “I’m anxious about this or I’m worried about this.” a child feels that vibe and they can resist almost immediately. And the parent says, “I don’t know why they’re resisting me all the time.” The parent will back up and say, “How can I convey with my, maybe, calmer demeanor, my warmer demeanor, my good humor demeanor. That’s my job as a parent to get somewhere aimed toward that I’ll-never-be-perfect at it, but whatever I can do to aim for that, may communicate to my child that I really do believe in them. And that will help them move forward in ways that are best for them.

LUANN: With some of the teens I work with, a theme that comes up is, “I wish my parents would stop trying to fix it. I just want them to hear me. I want them to hear what this felt like for me. I can figure it out. I can address this problem, wherever it is, at school or lots of different scenarios. I don’t want mom to zoom in and make it all go away. I just want to be heard.” That holds so much power, just being heard and validated. And then, support the solution they’re coming up with. If they want parents involved, great. But if not, it can be really, really hard to stand back and let them deal with it. There was, this is personal life, but when one of my children was in high school, we were out in the community and this child of mine had recently come out as queer in his peer group so he was out at high school. And somebody recognized him from school and yelled something really vile out the window. And I said, “Do you know those kids?” And he says, “Yeah. I know them from school.” I said, “You don’t have to put up with that. I’m ready for war. I’m ready to storm into the principal's office and say this is not acceptable, deal with this.” And he’s like, “Mom, no. I got it. No. I don’t need that.” And he didn't. He was okay. It was a horrible thing to go through and hear. But he had the resources and the tools to deal with it. He didn’t need me to rescue him. And that scenario can show up in so many ways. Just listen. If they need help, hopefully they’ll ask for it. And if they say, “No. I don’t need you to fix this.” We need to honor that too. I try to do that as a mom.

JEN: Do you guys hear, ever as therapists, from parents this idea of, “Alright. We’ve been coming here for two years now. Is it almost done? Have we almost sorted it?” That’s what this quote made me think of is that parents are trying to rush the process of therapy. Is that a thing that happened?

LISA: Oh, I think parents always would like to rush the process of therapy. And therapists would too. But we recognize that these things happen in the course of everyday problems, everyday conflicts, everyday upsets. As therapists, we create what’s called a treatment plan. And it can be sort of overarching. So two years later, we may still be working on those same things but applying them in more and more complex ways. And we see families benefit from that. So there’s no shame in being in therapy for a while. And there’s no shame in only wanting it for a short time.

JEN: Becca, do you have thoughts on this one?

BECCA: A lot of times, I feel like this happens in particular when parents are focusing on their kids' issues, their kids' challenges, and wanting them to resolve. And a lot of time, that desire and need of the parents, they think of wanting it to resolve is for their own comfort. And the more they are focused on that, the more they’re trying to, yes, fix their child. And so sometimes when I see that, I try to redirect the parents and say, “Okay, what problems is this really causing for you? What’s the real objection that you have?” And sometimes it’s like, “Well, I want my kids' lives to be X, Y, and Z.” I’m like, “Okay. But that’s their choice. What’s the real problem that you can actually say is part of your life?” And if there’s anything like if it’s something like, “Well, my kids room is dirty and so we don’t have any dishes because they’re all in his room.” Okay, let’s just talk about how can we give you the autonomy to keep your room however you want and ensure that we have enough dishes in the kitchen to put dinner on the table. Talk about that as opposed to just we have to get this 100% resolved and kind of give them fixated on it.

LISA: That’s good advice. And, as an overarching idea too, it’s always good to have parents ask their children, “What does your best life look like? Tell me what your best hope for your life, five, ten years from now is.” and generally, children will talk about wanting to have the kind of life that is actually a healthy, good life. And so parents can have the sense that their children are working toward that and that they just have to keep picking at the leaves in order to help their children. They can actually believe in what their children believe in as well.

JEN: I like that. When you know the long-term goal is not to stay stuck, I’m sure that’s comforting. All right, well, before I let you guys go, I’m hoping that you’ll each take turns and just speak directly to the parents and sometimes we have grandparents and aunts and uncles and stuff who are listening also. Anyone who’s mentoring or loving these queer teens and children. But offer us up your best tips. Anything that hasn’t been covered that you heart-to-heart just want to tell parents.

LUANN: Being queer is not an obstacle to your child’s happiness and success. Sometimes we fear that it will be because of so many pressures from so many different places. But there is absolutely beauty available to your kids.

JEN: Thank you for that, Luann.

BECCA: I guess something I would say to parents of queer kids is that once they get beyond their initial reaction which may include shock, fear, anxiety, all those things. Not wanting to begrudge any parent of their feelings from that perspective. But what I would like to tell them is, having a queer child is a gift. And it’s an opportunity that other parents don’t have. It will change you. It can change your life. It can change the way you see everything and respond to other people for the better. And so as parents, to look for that gift, to look for where those positives are showing up in their life.

LISA: I love that.

LUANN: I do too.

JEN: Thank you, Becca, for that.

LISA: I think one of the ways those positives show up are in the expansion of heart that a parent goes through. Most parents who have been in this place for a while will say they – now looking back – see how their heart was expanded, see how they shifted, and they would not go back to where their heart was before. There is something deeply loving about what happens when we make room for a child who has a world view that’s different from the one that we started out with. It expands us and it has the capacity to make us both loving and wise if we will let it.

LUANN: I want to add a little bit to my statement if that’s OK?

JEN: We’d be crazy not to take it.

LUANN: It is healthy and helpful for your child and your relationship with your child to celebrate their queerness.

LISA: That’s the perfect ending, don’t link it back. Put it at the very end.

JEN: I want to thank each of you for coming, for taking your time. I know you’re busy. I know you’re all working and managing families and lives on top of that. And I appreciate so much that you guys were willing to donate this time to help our listeners. Thank you for coming.

BECCA: Thank you.

LUANN: Thanks for having us.

LISA: We deeply value Mama Dragons, so thank you for inviting us.

JEN: Thanks for joining us here In the Den. If you enjoyed this episode, please tell your friends, and take a minute to leave a positive rating or review wherever you listen. Good reviews make us more visible and help us reach more folks who could benefit from listening. And if you’d like to help Mama Dragons in our mission to support, educate, and empower the parents of LGBTQ children, please donate at mamadragons.org or click the donate link in the show notes. For more information on Mama Dragons and the podcast, you can follow us on Instagram or Facebook or visit our website at mamadragons.org.